All this week, Ryan is covering the movies and moments of the 50th Ann Arbor Film Festival in the Michigan Theater, sharing his experiences of the festival. Share your thoughts and stories in the comments and enjoy a great week of experimental film!

After five days of marathon experimental film viewing at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, your brain feels a bit like it's been turned to mush. Your eyes buzz at night like they've been used as some mad scientist's plasma globes, but there's a sensation too like you're really starting to just "get it."

The whole thing. Why we're there. Why filmmakers fly in from Boston, from Finland, from England, from California to here. Why the festival has survived for 50 years and why people kept coming back to sit in front of a screen and feel elated, confounded, challenged, ecstatic and changed. You sort of start to see patterns of representations, ways that experimental filmmakers can change your perception of the world.

How they can make a regular thing strange and then pluck a entirely new meaning out of it.

It's a singular experience: watching avant-garde art movies in a massive movie auditorium with a crowd of people. You'll get the occasional heckler who feels compelled to express how boring and ordinary he is with an exaggerated yawn or a sarcastic clap. But on the whole its a group of entranced, eager and excited people who, like you, are just "into it."

If you take your eyes away and glance down from the screen during a film and see the light flickering off the sea of faces, there's something almost like a religious experience going on here. Like sitting around a campfire sharing dreams. You wonder: how is everyone else experiencing this? Are they getting any of it? What do they think of this scene?

Or at least I did.

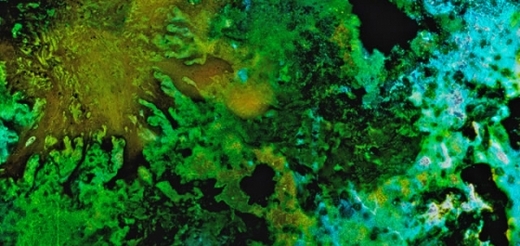

Still from Jennifer Reeves' "Landfill 16"

I wished at times I could hop through the audience and whisper questions into everyone's ear without pissing off a lot of nicely dressed people and being asked to leave.I liked to ask myself this question at the end of every short screening: was this something my mind could have even conceived? I'm not at the moment a practicing filmmaker, but I've made short movies in college and tinkering around with video at home.

If I saw this copse of trees in the autumn or that sliver of light reflected through a broken, dusty window, could my mind have found some of these same themes, conceived some of those same images of wonder?

Most of the time the answer is resoundingly no. Which is fantastic.

The best films were the movies that felt so totally outside of the realm of my own thinking, so utterly foreign to the way my brain works and I think creatively, that it felt as if I was encountering some entirely new way of thinking and seeing. And yet, somehow, they remained resolutely recognizable and rich and human. That's great art.

Still from Robert Todd's "Within"

The films in competition on Saturday night for whatever reason felt to be uniquely evocative, and several of them spoke powerfully to one of the many themes that ran through this year's festival: the death or waning of movies done on actual, physical film.

As one of the essays pointed out in the early pages of this year's program guide, 2012 was the year Eastman Kodak filed for bankruptcy, a year when it seemed that the hopes for celluloid were dim.

And yet at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, there were films that existed only because of the unique and tangible properties of a roll of 16 or 35 or Super 8mm film.

The most powerful example of this was Jennifer Reeve's "Landfill 16." Faced with a mountain of outtakes destined for a landfilm from her previous film, Reeves decided to bury the film stock in her backyard, let the natural process of enzymes and decay work on the face on the film, then dig it back up, chemically stain some parts of it, hand-paint others and feed it through a projector reel sometimes two frames on top of each other to generate incredible images of color and decay.

The prolific Boston filmmaker Robert Todd screened his new film "strong>Within" and revealed afterward on stage in the Q&A how all the editing, the fades and superimpositions where done in the moment, in camera with only a single actual cut in the entire film. What resulted was a recording of his thought process of his sense of discovery peering through the viewfinder and reflections and leaves and light.

While there is obviously a heavy degree of practiced artistry, Todd's technique and the fact that in camera he was able to put together a piece without really seeing the thing as he worked on it lends this organic and personal honesty to the film that would not be as genuinely achievable working in Final Cut Pro on your computer putting together the movie together frame by frame. You lose that sense of "in the moment."

Maybe that's what those people who dread the coming of the digital age are afraid of losing, this ability to work and play and make art from the uniquely filmic properties of a piece of Kodak 16mm film. If so, the Ann Arbor Film Festival remains a bastion of that kind of filmmaking. It's one of the great things the festival has the power to display.

And yet the digital revolution is coming or is here or has long since arrived and people are just gradually coming around to acknowledge it. The beautiful work of movies on film stalwarts aside, clearly every kind of artistic medium has its own physical foibles that can be utilized and tinkered with to make great art.

Semiconductor's "20 Hz" is a great example of that. It's the visualization of data collected as a solar storm hits the Earth's atmosphere. It looked something like a tight series of concentric circles of flower petals, made out of static and jumping light, like watching a pool of water bounce on top of loud speaker, shimmering and shaking with each thwack of the bass.

Another digital work Evan Meaney's "Ceibas: Epilogue - The Well of Representation" was a recreation of 1979 film "Gloria!" made with the ROM files of old video games put on his computer. Meaney programmed in the story, tinkered and played with the code until he learned its idiosyncrasies and all the ways it could fail. So he designed it to mess up, to glitch, to host a whole field of bugs, to crash and go haywire. As he recorded it, the mistakes became part of the narrative and fit into the story and also just looked really, really cool.

We're at a moment then, in the history of film and the film festival where the medium is changing, the old is threatened and the new is trying to find its place. And it's one and all heady and amazing stuff.

lee corso thanksgiving appetizers greg jennings thanksgiving recipes thanksgiving recipes mashed potato recipe mashed potato recipe

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.